Alma Foundation: Improving Indigenous Education in a Culturally-Responsive Manner

Garfield Gini-Newman, Ian McGroarty, Alan Harman, Laura Gini-Newman

Abstract: Rural Indigenous communities face significant hurdles in balancing educating children to meet the challenges of a rapidly changing world while preserving their cultural values and traditional ways of life. In this chapter, the authors share the story of the Alma Children’s Education Foundation, a non-profit organization working with Indigenous communities in Peru and Bolivia to improve the quality of education for Indigenous children. The chapter explores the nature of the educational challenges, Alma’s unique approach at delivering culturally-relevant, project and play-based learning that supports the mandated state curriculum, and the impact of the work on children, their families and their communities.

A multitude of well-meaning organizations are working in developing countries attempting to support the development of children. Often these efforts focus on improving educational outcomes for economically impoverished children. The challenge all such organizations face is providing culturally-sensitive supports that respect the children as learners in a specific geographic and cultural context. Rarely do these organizations incorporate, let alone acknowledge the informal education that has existed in these communities for centuries. Too often, efforts at supporting the education of children in these contexts is fraught with western assumptions of success and the measure of the projects impose western values. The programs are usually delivered in a manner that is foreign to the indigenous way of learning. One organization that makes a concerted effort to avoid such pitfalls is the Alma Foundation. For the past nine years Alma has worked with remote Indigenous communities in Cusco (southern Andean) and Loreto (Amazon jungle) districts of Peru and the Beni (Amazon jungle) region of Bolivia to nurture critical and creative thinking though culturally-relevant play-based projects.

Understanding the challenge

Beginning in 2019 Peru has embarked on an ambitious plan of educational reform that diminishes the role of content while shifting the focus to a competency-based approach. These reforms are intended to improve the perennially low achievement of Peruvian students. In 2013, OECD ranked Peru last in reading comprehension, math and science. The 2016 PISA rankings were only slightly better with Peru being ranked 64th out of 70 countries. The low national scores tell only part of the story. Indigenous students generally fare much worse than their non-Indigenous counterparts. For children seven years of age, only 13 percent reached required math levels and only 30 percent reached required reading levels. (https://borgenproject.org/state-education-peru/)

There are several factors that contribute to the poor educational outcomes among Indigenous children in Peru including:

- Lack of funding for bilingual education (most Indigenous children arrive at school speaking Quechua with little command of the Spanish language of instruction)

- Isolation of the Indigenous communities make it challenging for many students to get to a school

- A centralized curriculum that reflects little cultural or geographic relevance to the lives of Indigenous children in remote rural communities

- A strong bias against girls’ education as a family priority

- Lack of support in the home from generally poorly educated parents

- Many Indigenous children under the age of five suffer from malnutrition

- 34 per cent of children between the ages of five to seventeen participate to varying degrees in the work force including responsibilities in rural communities for helping to care for livestock such as Alpacas (resulting in erratic attendance at school for many children) (http://www.oecd.org/dev/inclusivesocietiesanddevelopment/youth-issues-in-peru.htm)

- The quality of teachers tends to be poorer in rural jurisdictions and poorer still in remote Indigenous communities

As with many countries around the world, Peru is embarking on an effort to modernize learning with a shift from didactic instruction focused on a fixed body of knowledge to a competency-based curriculum with a focus on critical and creative inquiry. This dramatic shift allows for a more culturally-relevant pedagogy that will better meet the needs of its Indigenous population but will require a significant investment in teacher training to ensure the goals of the re-imagined education system are achieved.

Establishing culturally-responsive (relevant) goals

Improving Peru’s education system must focus on diverse needs of its population. To do so requires a redefining of the measures of success. Relying solely on the international test scores as a measure of success fails to respond to the needs or rural Indigenous communities. While literacy and numeracy are universally important educational goals, they are more importantly a means to children’s meaningful engagement within their communities. Consequently, a culturally-relevant pedagogy must draw upon the local Indigenous communities as a focus for instruction and a vehicle through which children become literate and numerate citizens. Furthermore, thinking should reside at the core of all learning to ensure both competencies and concepts can be transferred in to new contexts. As Indigenous communities adapt to a rapidly changing world, they will need their youth to become adept as problem solvers and innovators within the contexts of their local and regional communities to be able to respond to global issues that have local consequences.

When we talk about education based on local context or wisdom I think that we are summoning the past generations’ wisdom and the knowledge learned from the local land, weather, and animals. The information is integrated into narratives, songs, interactions, and cultural practices. This is how knowledge is shared and imparted and therefore defines “literacy” in the communities where we work and any place where oral traditions are strong. We try to make this literacy the core of our pedagogy. Because it is based on the local place it is easily experiential which makes it fun, relevant and meaningful. Sometimes we use books, cameras, and computers but only after information is gathered from traditional sources through, essentially, storytelling.

Alan Harman, Founder Alma Foundation

https://www.almafoundation.ca/the-value-of-story/

The Alma Children’s Education Foundation

The Alma Foundation was created by Alan Harman after a lengthy family trip through South America in 2008. He was deeply moved by the economic poverty and social circumstances he experienced in remote Indigenous communities in Southern Peru and was inspired to help improve the quality of life there. After consulting development experts in Peru and Canada, he decided that investing in early childhood education would provide the greatest opportunity to improve well-being over the long term. He developed a set of guiding principles that he felt would have a sustainable impact and founded the Alma Children’s Education Foundation in 2010 based on those principles.

Since then the charity has developed its own unique play-based and project-based curriculum focused on critical thinking. The curriculum is derived 100% from local context, culture and language.

Alma’s focus on transformative goals in a culturally-relevant context

From its inception the Alma Children’s Education Foundation has eschewed traditional measures of academic success which are commonly focused on memory, compliance and replication. Instead, Alma focuses on more transformative goals such as critical, creative and collaborative thinking and social responsibility. By nurturing students’ ability to think and solve problems in innovative ways, children are able to transfer the learning that takes place through the projects to new context within their communities. Students’ proficiency in literacy and numeracy are also developed through a thinking approach to learning and within culturally relevant contexts. In fact, what distinguishes the work of the Alma Foundation is the manner by which they position learning at the intersection of rich thinking, authentic culturally-relevant projects, and hands-on community-based learning.

Furthermore, Alma’s educational philosophy is grounded in harmonious personal, social, and environmental values found in the students’ respective Indigenous cultures. As access to information and humanity’s ability to manipulate our environment have become exponentially more powerful, the focus on inner human development becomes ever more pressing and necessary in the classroom. While students are tasked with complex reasoning around cultural and academic activities and content, they are also challenged to practice the ideals of their cultural value system. Personal introspection, social and environmental interconnectivity, resilience, and compassion are larger overarching ideas that guide much of the activities in which the students are engaged. Sometimes they are clearly highlighted, sometimes they are subtle, but they are always necessary for the successful completion of the academic challenge. In Alma classrooms, students must demonstrate not only acquired knowledge, but utilize it to positive ends.

Through such an approach, Indigenous students confront the unique challenge of finding their sense of self at the intersection of distinct and constantly evolving cultures: one specific to their Indigenous identity and the others to their more common regional, national, global and generational identities. Attempts to reinforce and structure strictly state-mandated academic standards push students away from their traditional culture, ignoring its relevancy and meaning in their day to day lives; while attempts to promote and preserve strictly traditional indigenous culture and learning in the classroom leave the students isolated from the larger culture and unprepared to thrive within it. Alma’s unique methodology, however, provides the space where Indigenous students can use state-mandated academics to implement and complete stimulating cultural projects, allowing students to both value and practice their traditional Indigenous culture while also enriching their academic experience in state-mandated curriculum. Students find themselves connected to both their traditional culture and the larger surrounding cultures, in all of which the students are participants. Alma’s methodology allows students to develop and use their gifts to contribute to their personal, communal, and common growth, promoting a strong sense of self as well as meaningful connections with their local, regional, national, global, and generational communities.

“Gracias al proyecto, tengo mejor lucidez en cuanto a la finalidad de la educación, y creo firmemente que es el de darle a los estudiantes las herramientas necesarias para comprender el mundo en el que están creciendo y que les guíen en su actuar, poner las bases para ser personas capaces de intervenir activa y críticamente en la sociedad, además de desarrollar los conocimientos, capacidades, habilidades y actitudes necesarias para conseguir una realización personal para ejercer una ciudadanía activa, incorporándose en la vida adulta de manera satisfactoria, ser capaces de adaptarse a nuevas situaciones y de desarrollar un aprendizaje permanente a lo largo de su vida.”

Litze Rivero Murakami- Alma Teacher- Beni, Bolivia

(“Thanks to [Alma], I am clearer on the purpose of education. I firmly believe that it is to give the students the necessary tools to understand the world that they are growing up in and that they guide them in how to act; to provide a foundation to intervene proactively and critically in society; to develop the knowledge, capabilities, abilities, and attitudes necessary to achieve self-realization and exercise active citizenship, incorporating them into their adult lives satisfactorily; to be capable of adapting to new situations; and to develop a state of permanent learning throughout their lives.”)

“Noqa munani yachayta llaqtaypi ruwaykunawan, niymancha tipaykunawan, wasiruwaykunawan, imaymanakunamanta. Ichaqha yachaykunata mat’ipaspa, chaymantapis proyectopi tumpata samayuq yachaywasimanta lluqsipa.”

Rodolfo- 5th grade student- Cusco, Peru wasiruwaykuna

(“I like to learn through activities from my community, like weaving and house building, while learning academic courses like we do in the [Alma] project because it lets me relax a little after my classes in school.”)

Parental Involvement

It is common to hear that a large obstacle to quality education in Peruvian and Bolivian Indigenous communities is that parents care more about their crops and animals than their children’s education. Alma’s experience has confronted this idea over the years and come to the understanding that this is not the case. For the majority of parents, formal education is a foreign world, and they are uncomfortable stepping into a proactive role as formal educators. How can someone who doesn’t know how to read teach a child to read?

To ensure parental involvement, Alma uses a two-pronged approach. The first is basing all academics within culturally relevant projects, which often require the input of parents who know more than the students or teachers about different traditional activities. The cultural projects illuminate the math, science and communication skills necessary in traditional weaving, planting, construction, cooking, etc. that the parents, often unconsciously, excel in. In addition, Alma teachers visit the parents of every student in their homes twice a year, along with two public meetings per year, during which the teachers present parents with their children’s digital progress portfolio and teach them strategies on how to help their children improve in areas like communication, math, information retention, analysis and evaluation, creative thinking, etc. Both parents must be present for all four meetings and then our teachers follow up afterwards to monitor and assist with student and parent progress.

It is hard work for parents who, in almost every case, have little or no experience with formal education and cannot read or write themselves. Nevertheless, Alma develops strategies with them in mind, and creates materials so that the parents can lead the activity without needing to understand the course content involved. Flash cards to test mathematical concepts, literature talking points to encourage analysis and evaluation of the text, image-based reading comprehension activities, etc. are all educational tools that can be implemented by parents in their homes.

The impact of involved, proactive parents is a key, and often neglected factor in students’ success. And once parents see their positive impact and their teaching abilities, they are encouraged to continue and do more. Parents do care, but they need the right tools and strategies to allow them to get involved.

“Yo, como madre, lo que quería decir es que nunca me había preguntado cómo es el funcionamiento en el aula actualmente, como estaría mi hijo Daniel dentro del aula, qué hace y cómo lo hace; pero la verdad es que viniendo aquí a las reuniones y entrando a la clase me doy cuenta que es totalmente diferente a lo que nosotros hemos tenido cuando éramos pequeños. Y no solo diferente, si no, como más amplio, como más humano, bajan al nivel del niño y no esperan que el niño suba al nivel donde están ustedes, enseñan de manera divertida y así los niños no tienen miedo de aprender o de demostrar lo que aprendieron, porque no solo es tener conocimientos si no compartirlo y verlo de otra forma, como más amplio, como más bonito, que atrae, porque cabe todo, no solo lo que hay en un libro, sino lo que pueden aportar ellos como niños, como gente que piensa y también puede opinar”.

Leonilda Semo- Mother- Beni, Bolivia

(“As a mother, I would like to say that I had never asked myself how classrooms currently function; how my son, Daniel, is doing in school; or what he is doing and how he does it. But honestly, coming here to the [Alma] meetings and visiting the [Alma] classroom I realized that it is completely different than what we had when we were young. Not only different, but more open- more human. [Alma teachers] meet the children at their reality and don’t expect them to come to the reality of the teachers. They teach in a fun way so that the children aren’t afraid to learn or show what they’ve learned. Because [education] is not only to only have knowledge, but to share it and see it from different perspectives: more open, more beautiful, something attractive. In the end, it’s not only what is in a book, but what the children can give as children, as people who think and can have opinions too.”)

“Me agradada cuando los padres de familia muestran satisfacción y agradecimiento por mi labor como docente y se involucran en la educación de sus hijos ya que antes no pensaban de la misma manera, eran muy ajenos a las actividades académicas, con el tiempo y sobre todo gracias a las visitas a familia, comprendieron que también ellos podían apoyarlos en cuanto a las dificultades que presentaban sus hijos con ayuda de estrategias que les sugería, luego se dieron cuenta que podían apoyar desde la casa y juntos hacer que sus hijos puedan salir adelante superando sus dificultades.”

Gustavo Aparicio Camani- Alma Teacher- Cusco, Peru

(“I like when parents show satisfaction and gratitude for my effort as a teacher and when they get involved in their children’s education. [Before the Alma project], they didn’t think the same way. They were distant from academic activities. However, over time and more than anything thanks to the home visits, they came to understand that they too can help with their children’s difficulties using the strategies that I would offer. They came to see that they can help [their children academically] from the home and that together we can help their children advance and overcome challenges.”)

Learning through culturally-relevant community-based projects.

The Alma Children’s Education Foundation supplements the regular school day by offering afternoon learning opportunities in rural Indigenous communities in Peru and Bolivia. The projects are designed for deep learning through a sustained inquiry approach where students engage in a rich community-based project over several weeks. Multiple subject areas including math, science, cultural studies and literacy are authentically woven into the projects as scaffolding that enable the students to develop thoughtful responses to culturally-relevant challenges posed by the projects. Below is a sampling of the projects implement by Alma to promote deep and engaged learning.

Sharing community stories through Andean Weaving

Weaving is an essential part of traditional Andean culture dating back over 2,000 years. Aside from its functional purpose, Andean weaving celebrates Pachamama – Mother Earth – and reflects concepts relating to the natural world such as space, time, growth and the interrelatedness between species. Elizabeth Conrad Van Buskirk of the organization Cultural Survival, notes that Andean “weavers pass on their knowledge, not by writing, but by the process of person-to-person communication, watching and practicing” and warns that the Peruvian textile tradition could be lost in this generation. (https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/preserving-andean-weaving-center-traditional-textiles) In the Alma projects, efforts to preserve traditional weaving techniques are combined with cultural studies and mathematics. Children learn how to weave from community parents and elders. In school they are asked to design a pattern that communicates an aspect of their community to others, for example geographic features or important animals in their culture. The children also learn about the geometric properties of various shapes and types of transformation that can be used in creating their story of their community through weaving. Foundational concepts such as addition and multiplication are practiced as children reason their way to the creation of mathematical patterns using symbolic geometric shapes. Conceptual and symbolic mathematical reasoning play a central role in the design of effective Peruvian weavings.

Developing an Virtuous Eco-garden

In both Peru and Bolivia, malnutrition is an obstacle to learning for rural Indigenous students. Though the nutrition initiatives of local and national governments are improving, and because nutrition is not a direct focus of the foundation, Alma created an eco-garden project where students are challenged to cultivate a virtuous eco-garden to promote a healthy and balanced diet in their school. As always, the project was developed to promote critical and creative thinking around state-mandated academic content and cultural values. In this case, the virtuous eco-garden is rooted in the indigenous Quechua tradition of showing gratitude and respect for Pachamama (Mother Earth).

Instead of only researching science content, students also implement ancestral knowledge and judgment strategies to define the best place to cultivate the eco-garden and to design a significant manner to ask permission from the earth to do so. Instead of only drilling math problems, students reason through mathematical concepts, traditional techniques, and evaluative strategies to harvest and store the products from the eco-garden, formulate optimum harvest quantities and uses for every product, and ensure that nothing is wasted. Instead of only writing a garden management plan, students analyze science content and effective communication skills to design the efficient management of the eco-garden, while taking into account how to show gratitude to the garden and give back in meaningful reciprocity.

The project reinforces state-mandated academics and Alma’s analytic and evaluative strategies, as well as steer students towards a deeper focus on traditional harmonious values.

Creating a mural map of the community for visitors

The meaning and importance of place is a foundation of many Indigenous cultures throughout the world, including the Indigenous communities in Peru and Bolivia where Alma works. In the Mural Map project, students are tasked with demarcating their communities’ borders using important landmarks, locating and properly distributing areas of the community (public spaces, houses, roads/paths, habitats for domesticated and wild plants and animals, etc.) according to the scale they develop, effectively implementing and communicating census information, and including anecdotes and traditional stories relevant to different places identified on their maps.

They learn and practice proportions, translate non-standard to standard measurements, develop their creative and historical writing skills, graph numerical data, design effective symbols, create habitat descriptions for domestic and wild plants and animals, and much more. But most importantly, the students shine a spotlight on what their respective communities have to offer, what happens there, and why they are meaningful to the people who live there and valuable those who don’t.

In a region where rural Indigenous peoples still tend to be isolated and marginalized, it is beautiful to see the students speak of their place- their home- and demonstrate its importance and cultural value.

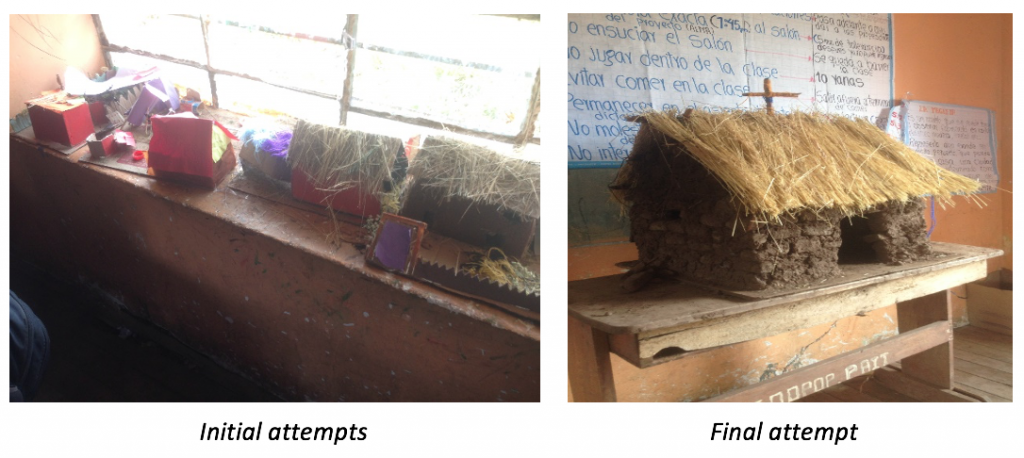

Learning to construct a traditional home

This project is specific to Alma’s students living in the Cusco region of Peru, where traditional Andean house building, wasichakuy, is still practiced. The students are challenged to investigate the traditional and current house building methods that exist in their community and use that information to build a model house out of local materials. They learn about native and foreign plants and animals related to building materials and food served during the activities; they learn about traditional techniques and why things are/were built in specific ways; they use language skills and math to plan the materials needed, set the specs for the build, structure meaningful interviews with community elders, and assign responsibilities among themselves for the build.

However, a key component to this project, as with all of Alma’s projects, is the opportunity for students to try, evaluate, and try again. Almost universally, students’ first model house falls short of the evaluative criteria they establish for a high quality home and they must deepen their investigation and improve the implementation of the academic content in order to rebuild their model house.

Alma Children’s Education Foundation’s Impact on Indigenous learning

In 2017, to assess the efficacy of their work in various communities, Alma conducted a series of interviews with parents and students. Among the findings from the interviews were reports from parents that their children’s participation in the Alma project had improved their learning, and that the students actively shared their learning at home (something that was not occurring in the regular day school). This allowed parents to play a more active role in their children’s learning. They also reported that their children’s academic achievement was above those of students from other communities that were not involved in the Alma Children’s Education Foundation’s projects. Parents also noted that the home visits offered by Alma allowed them to play a more meaningful role in supporting their children’s learning. One parent noted that her daughter was performing at a noticeably higher academic level than her son who did not have the opportunity to participate in the Alma project. She also reported that her daughter is now excited about going to school and sad when the project is not running. Parents explained that an impact of Alma’s work in their communities was a building of important relationships of trust with the Alma teachers and that led to improvement in learning, particularly in mathematics. (Gini-Newman and Gini-Newman, 2018)

Conversations with and observations of the children involved with Alma revealed that they were eager to stay after the end of the regular school day to take part in the Alma projects and in fact, during a teachers’ strike when there were no classes to attend, students would still walk, in some cases for over four hours, to school for the afternoon to take part in the Alma projects. The children were also observed to actively and eagerly take part in the project work during both the instructional time led by Alma teachers and the hands-on time that was guided by the Alma teachers. Conversations with children who were involved with the Alma projects revealed that they were more intellectually engaged when they were invited to apply their learning in thoughtful and authentic contexts unlike their regular school day where learning was primarily through rote memorization and replication.

Concluding thoughts and next steps

The innovative and culturally-relevant approach developed by the Alma Children’s Education Foundation is making an important difference one community at a time. Its successes are beginning to be noticed. Recently Alma has been invited by the Peruvian Ministry of Education to develop a teacher training program that will help public school teachers to embrace this rich pedagogical approach. Beginning January of 2020, Alma will train 680 state teachers working in 150 primary schools with 11,483 students. Such a transformation in curriculum design and implementation will be an important step forward in the quality of education delivered to Indigenous children in rural and remote communities in Peru.

Alma Children’s Education Foundation’s Impact on Indigenous learning

In 2017, to assess the efficacy of their work in various communities, Alma conducted a series of interviews with parents and students. Among the findings from the interviews were reports from parents that their children’s participation in the Alma project had improved their learning, and that the students actively shared their learning at home (something that was not occurring in the regular day school). This allowed parents to play a more active role in their children’s learning. They also reported that their children’s academic achievement was above those of students from other communities that were not involved in the Alma Children’s Education Foundation’s projects. Parents also noted that the home visits offered by Alma allowed them to play a more meaningful role in supporting their children’s learning. One parent noted that her daughter was performing at a noticeably higher academic level than her son who did not have the opportunity to participate in the Alma project. She also reported that her daughter is now excited about going to school and sad when the project is not running. Parents explained that an impact of Alma’s work in their communities was a building of important relationships of trust with the Alma teachers and that led to improvement in learning, particularly in mathematics. (Gini-Newman and Gini-Newman, 2018)

Conversations with and observations of the children involved with Alma revealed that they were eager to stay after the end of the regular school day to take part in the Alma projects and in fact, during a teachers’ strike when there were no classes to attend, students would still walk, in some cases for over four hours, to school for the afternoon to take part in the Alma projects. The children were also observed to actively and eagerly take part in the project work during both the instructional time led by Alma teachers and the hands-on time that was guided by the Alma teachers. Conversations with children who were involved with the Alma projects revealed that they were more intellectually engaged when they were invited to apply their learning in thoughtful and authentic contexts unlike their regular school day where learning was primarily through rote memorization and replication.

Concluding thoughts and next steps

The innovative and culturally-relevant approach developed by the Alma Children’s Education Foundation is making an important difference one community at a time. Its successes are beginning to be noticed. Recently Alma has been invited by the Peruvian Ministry of Education to develop a teacher training program that will help public school teachers to embrace this rich pedagogical approach. Beginning January of 2020, Alma will train 680 state teachers working in 150 primary schools with 11,483 students. Such a transformation in curriculum design and implementation will be an important step forward in the quality of education delivered to Indigenous children in rural and remote communities in Peru.

References

Gini-Newman, Garfield and Gini-Newman, Laura (January, 2018) Alma Foundation Report, prepared for the Alma Children’s Education Foundation, January 15, 2018.

Harman, Alan, (November 2018), The Value of Story, Retrieved from https://www.almafoundation.ca/the-value-of-story/

Marino, Eleni (June, 2014) The Borgen Project, The state of education in Peru, Retrieved from

https://borgenproject.org/state-education-peru/

OECD, Key Issues affecting Youth in Peru, Retrieved from

http://www.oecd.org/dev/inclusivesocietiesanddevelopment/youth-issues-in-peru.htm)

Van Buskirk, Elizabeth Conrad (1999).

Preserving Andean weaving: the center for traditional textiles of Cusco, Retrieved from https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/preserving-andean-weaving-center-traditional-textiles)

Authors:

Garfield Gini-Newman

Associate Professor,

Department of Curriculum, Teaching and Learning

Ontario Institute of Studies in Education, University of Toronto

252 Bloor St. W,

Toronto, Ontario

Ian McGroarty

Program Director,

Alma Children’s Education Foundation

Urb. Quispicanchi, Calle Venezuela K-10,

Cusco, Peru

Alan Harman

President, Alma Children’s Education Foundation

19 Kingswood Road

Toronto, Ontario

Laura Gini-Newman

Math Consultant, Coach and Facilitator, TC2;

Co-founder Flourish Co.

4 Damascus Dr.

Caledon East, Ontario